Prince Harry and Meghan Markle at the premiere of "Bob Marley: One Love" in Jamaica.

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle made a surprise red carpet appearance.The Duke and Duchess of Sussex were spotted at the premiere of the music biopic "...

Read More

In October 2017, during the height of #MeToo, I was sexually assaulted by my roommate. We lived together for about seven months, during which time he quickly became one of my best friends. I had been assaulted before, but this time it was because my assailant was not a stranger lurking in the shadows. He was the one who brought me electrolyte water when I returned from Mexico with an upset stomach and shared childhood memories that brought tears to my eyes. He was the one with whom I could debate whether or not Bob Marley was a misogynist who expected his wife to sing in the background of a song he wrote for his new, younger girlfriend. As those arguments unfolded and my deepest fears were revealed - that at the heart of the man, he did not love women - he was protective, dependable, and loving. Until one night he wasn't.

Immediately after the attack, only my grief outweighed the betrayal I felt. But like many victims of sexual assault, I tried to minimize the emotional impact: two months, I arbitrarily told myself, and in two months everything would be back to normal, because I figured that 60 days would be enough time to get myself together. But more than that, I had the illusion that my pain deadline was approaching.

It was exactly two months after the seizure that the house of cards came crashing down. The episode was so shocking that it forced me to be honest about my situation: I sobbed myself to exhaustion in bed at night, sometimes crying for 10 hours straight. I drank alone most nights to make it through the night. I moved out of the apartment I shared with my assailant, but was unreasonably frightened that my new home would be broken into. My libido was atrophied and I was wondering if I would ever be able to have a healthy sexual relationship again. Simply admitting that question was enough to send me into a tailspin of anguish. All around me, #MeToo affirmed the anger of assault victims. I could empathize, but I knew that for me, applying anger to hurt would never be therapeutic. I needed help.

A few days later, I Googled therapists who specialized in sexual trauma and found an LPC (licensed professional counselor) just 20 minutes away. Every week we sat in leather chairs and sorted through my pain. When I told her how I had been told by close friends that I 'should have seen this coming' or that 'he may have just been agitated,' she assured me that I was not to blame. The therapist also assured me that I was not broken because I longed for the friendship I once shared with my assailant. She told me that this is a particular trauma reaction that is common in victims who know their assailant. It was as if my room was filled with smoke, and every week she would help me open another window.

In addition to traditional talk therapy, we also tried eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR), a form of psychotherapy designed to treat PTSD. EMDR is a psychotherapy designed to treat PTSD. For several months, I followed the light with my eyes, recalling the traumatic mental images of the attack and reconstructing them in a new, hopeful narrative. As I followed the tails of green dots weaving in the darkness, they unraveled the beliefs I had created to process the assault: that men do not love women, that men use cruelty and deception as a means of sex, that only women truly see my humanity.

These thoughts were bleak. But they were also a starting point that helped my therapist create a new story. While the green dot went back and forth, I repeated to myself the corrective statement: some men love women. Some men can love.

Eventually, I came to believe this new story somewhat. Three months into therapy and two months into EMDR, my despair was disappearing, but not completely. In fact, the despair had spread from my brain to my body. My trauma was stored as muscle memory. Just the thought of having sexual relations made my heart race with panic.

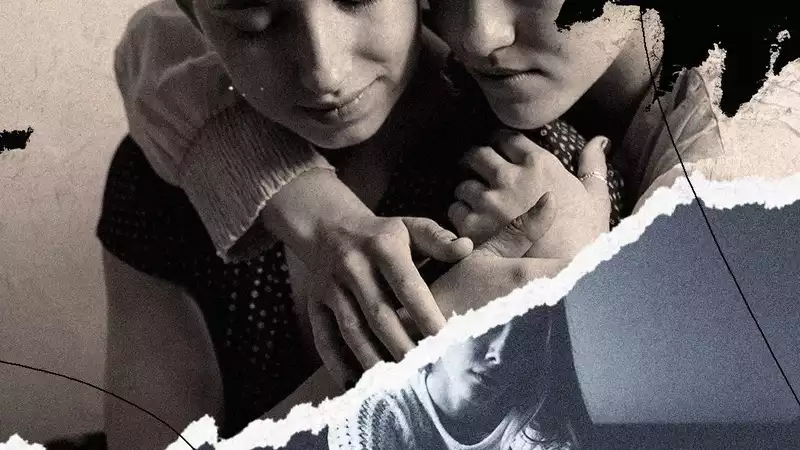

I needed to deal with the physicality of my trauma; I had read that cuddle therapy was sometimes used to treat PTSD. I was intimidated by the idea of one-on-one cuddle sessions, but I was more afraid that unhealed trauma would affect my future. So I went back to Google and found a trained cuddle therapist who specialized in assault rehabilitation. Ultimately, my goal was to be held with a spoon. This was the position I was in the night I was assaulted, and I feared that any future attempts to sleep that way with a man would spiral out of control.

Upon arriving for the session, the cuddle therapist led me to a soft futon bed covered with pillows. Since we had spoken on the phone before, she was able to better understand what I was hoping to get out of our work. We began slowly, with breathing exercises. Then we held hands. About 15 minutes into the session, we embraced. My anxiety eased, my jaw softened, and my heart rate slowed. Finally she came around behind me and pressed her cheek between my shoulder blades. As I sobbed forcefully, my body shuddered and seemed to release my bowels. I pulled her hand under my chin and curled up. She folded into the back of my knees.

I left feeling high. I was confused but released. After the assault, my entire body was enveloped in a forbidden force field that seemed to keep me from even having physical affection. It was not only fear of assault, but fear of opening up to someone who was duplicitous, insensitive, and grasping. Or worse, a nice person I trusted who would leave me as soon as I touched him and was devastated.

But my embrace therapist knew why I was there and was not put off by it. She knew why I wanted her to spoon me, she knew I would cry, and she knew exactly what to do when I did. Instead of feeling embarrassed, I felt watched and nursed. I saw a cuddle therapist several more times. Each session lifted my spirits, but I still felt a low-level whine of fear at the thought of sex.

Three months later, I heard about a healer who used a therapy called Body Memory Recall to release emotional trauma from the body through intentional touch; BMR is a form of Reiki developed in the West, based on the idea that, like cuddle therapy, the body can store painful memories and release them. BMR is based on the idea that the body stores painful memories and can release them, just as in embrace therapy. Before I could change my mind, I made an appointment for the next day.

In retrospect, I was testing myself. Unlike other therapists, this healer was a man. I knew I had to trust him if I was going to have a successful therapy session. It had only been six months since my meltdown with my male massage therapist. Logically, I knew that men could love women, and EMDR therapy had gotten me there.

But behind that uncertainty was the hope I had built through consistent work with my therapists. It was so valuable to me that when I slumped down on the BMR therapist's table, I relied on it fully. The therapist made it clear from the beginning that I was in control. Before starting the treatment, he asked me to circle the areas on my body diagram where I did not want to be touched.

I had to remind myself to breathe as he gently pressed his hands along my arms and stomach, acting like a poultice, bringing to the surface the sadness I had been bottling up. He was almost like a shaman, gentle and soft-spoken, not afraid, irritated, or dismissive of my pain. I burst into tears when he held my breastbone and moved his hand just below my left breast. He asked me what was in it for me, but I was crying so hard I could barely make out the words "my heart."

Something changed that day. While I approach the mystical with a certain seriousness, the process of actually being touched did not feel as shocking as the experience of being touched by a man; EMDR therapy showed me that men can love women, and that it is possible for them to love women. Had I not had other therapy in the months leading up to that session, the mere idea of working with men would have been impossible. The part of me that insisted on never being vulnerable to men again needed the most to feel safe with them. [My healing process is ongoing and I still have to work on healing (with the help of the LPC I meet with weekly), but I am not struggling. When the grief comes back, I let it take over. When anxiety strikes, I take a deep breath and reassess myself in the present.

I no longer worry about having sexual relations with men. I know that predators roam among us, but I also know that some men can and do love women. And I know that through much effort and many tears, men can love me too. Not because therapy "fixed" me or took away all my pain. But because therapy has taught me that it is safe to show my truths - each aspect of me - longing, anguish, joy, and hope - to the right man, a man I choose to trust.

If you or someone you know has been a victim of sexual assault or harassment and is seeking help, visit RAINN.org (opens in a new tab)

or contact us at [5].

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle made a surprise red carpet appearance.The Duke and Duchess of Sussex were spotted at the premiere of the music biopic "...

Read More

Taylor Swift is once again proving just how generous she is.At Sunday's Chiefs game at Highmark Stadium in Orchard Park, NY, the superstar made a grea...

Read More

Ken is not having a good day.Ryan Gosling is clearly pleased to have been nominated for Best Supporting Actor at the 2024 Academy Awards, but his achi...

Read More

Some A-listers like the wide open back of a black dress, but in Kendall Jenner's case, she likes the wide open front of a black dress (well, back, too...

Read More

Comments