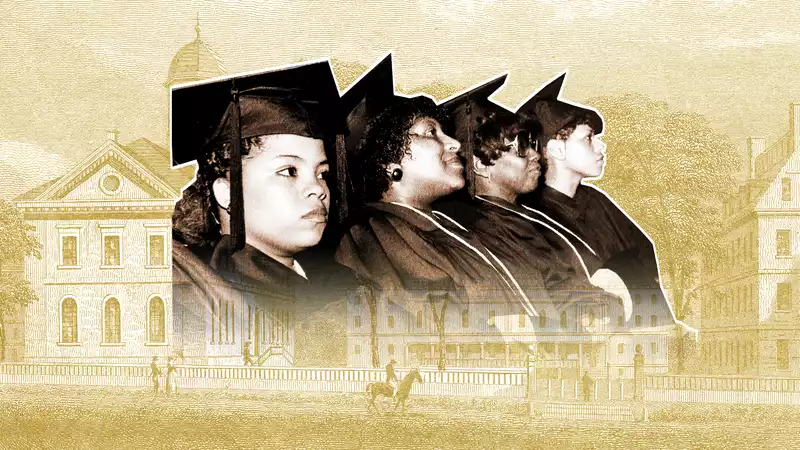

Without Affirmative Action, We Lose Everything

During my freshman year at Harvard, a new friend invited me to visit her in Manhattan before she returned home for Christmas. I am not certain how she got back to Manhattan from Cambridge, but I took the Hun Wah, a $10 bus from Boston to New York City. I had never been in a New York apartment before, much less one with multiple floors. When I arrived, she was in the middle of an argument with her mother. Apparently, her sister had installed a chandelier in the bathroom during a recent remodel, but she had not, and there was a huge uproar.

I have told this story many times over the past 20 years. It's a sure-fire crowd-pleaser story that fits nicely into people's (often accurate) image of Harvard University as a place for the super-rich. But thanks to affirmative action, I was there in the fall of 2000. I am the daughter of Cuban immigrants and a Latina from Miami-Dade County public schools.

Reflecting on the Supreme Court's decision to end race-based admissions at colleges and universities (including my alma mater, the defendant in this case), I thought about my friend with the chandelier. She was a very smart, legacy student, admitted from a private school that sends dozens of graduates to Ivy universities each year. There were many who questioned my admission to Harvard, but I don't think anyone questioned her right to be there. I have also thought about what it really means to be educated at Harvard. It is not just about the big "H" on your resume or the chance to be taught by a Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist. It is about the people you meet and the doors that open. It's about the chance to get close to power and thereby change the system.

Even in my first year, I knew I was getting a first-class education. I quickly learned that who you know matters. I watched from the sidelines as bankers, lawyers, and senators' kids got internships at banks, law firms, and Congress. Once I stopped being offended by it, I started paying attention. Through a referral from a Harvard classmate, I landed my first two jobs at a consulting firm. That magical network gave me the opportunity.

My classmates, the ones I stood in line at parties with and the ones I held up by my hair in the bathroom after the party was over, are now CEOs, governors, presidential candidates, hospital directors, Hollywood producers, and tech gurus. For better or worse, these are the people who shape the world. The diversity of the cafeteria was a stepping stone to the diversity of the boardroom, the White House, and the Supreme Court; consider what it means that CEOs, billionaires, and doctors are not completely homogeneous. My close friends in college were ethnically, socioeconomically, geographically, and racially diverse. And now some of us are in charge. (I co-founded the award-winning Impact Intelligence Agency, which works with some of the world's largest foundations and corporations on philanthropy and creating social change.) Thanks to affirmative action, we can now walk the same hallowed halls that were designed more than 400 years ago for white people who primarily owned slaves.

I do not condone a system of structural inequality in which elite colleges have such a profound influence over American life. I benefit from it, but I would rather live in a world where an Ivy League degree does not automatically confer extreme privilege on its graduates. But until then, I would prefer that access, power, and privilege be more equitably distributed and widely spread. To change the system, we need levers both on the outside and on the inside.

Affirmative action is not a perfect system, but it is one that has allowed me and others like me to succeed and prosper in a world that was not designed for us. My children, the great-grandchildren of Cuban pig farmers, would be legacy Harvard applicants, just like my chandelier friends, if they were to volunteer. Affirmative action, for all its imperfections, has had a generational impact.

This past March, I returned to Harvard Square to promote my book. I sat in an overpriced coffee shop, trying to remember what it was like there 20 years ago, balking at the price of a latte, waiting for a Crimson reporter to come to interview me. When she arrived, I told her how cool it was that a current student had sat with an alumna from almost 20 years ago, and that we were both Latinos. She was a neurobiology major, so there wasn't much I could do for her, but I told her to contact me if she needed anything.

Precious, scarce, and valuable connections are worth far more than expensive tuition. And America is poorer for it.

.

Comments