Life in the Gray Zone: Navigating Racial Injustice as a Mixed Race Person

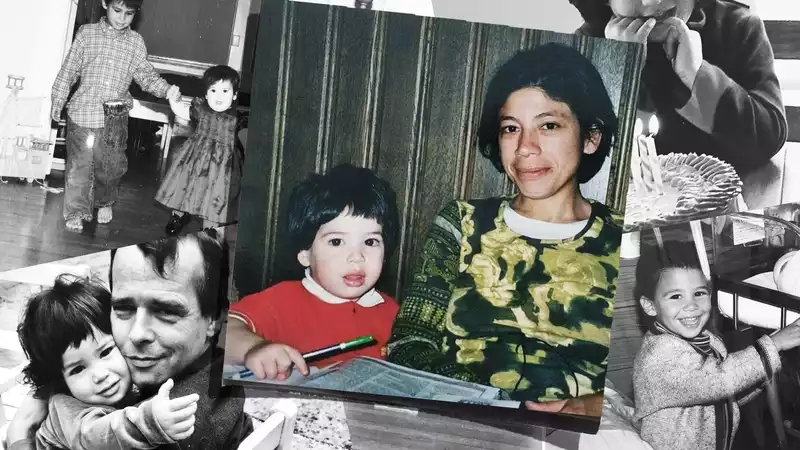

My mother always tells of the first time she noticed her children looking at race. I was chaperoning my kindergarten field trip, and as we walked, my (white, blonde) friend asked, "Why is your skin white while your mother is brown?" She asked. I did not answer. Instead, I took my mother's hand and kissed it. Until that moment, I don't know if I had realized that I did not resemble my brown-skinned mother or brother. Like many multiracial people, the question of where I belonged and who I was came primarily from outside the family. [When the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent protests brought police brutality back into the national spotlight, I wanted to speak out, but I didn't know where I fit into that conversation. Race is a frequent topic of conversation in my circle of family and friends. As a half-Latino, I feel deeply affected by acts of racism. Latinos have their own unique struggles in the United States that are relevant to each of us. But the topic that is happening around the world today is not about people of color. It is about Black Americans. Completely. As a half Latina passing for white, I cannot speak about the black experience in America. Yet, I felt an unrelenting empathy and a passion to engage. Still, something held me back. A few weeks ago, a girl I know posted this on Instagram." Dear white followers, your silence equals violence". I kept thinking about it. Is she talking about me? Does she know that I am not white?

On June 1, another friend, Miranda Rawlick, who is half black, wrote on her Instagram: "My racial ambiguity (not my words) has confused and offended people. And it became a sort of guilt-ridden camouflage in society that made me feel safe. It put into words a paradox that I have suffered from ever since that first walk with my mother's hand kissing mine.

Many multiracial people have the ability to go through life without being considered people of color. However, privilege and being multiracial do not always go hand in hand. My brother and I are the exact same mix, Nicaraguan and German, but he was targeted for racial discrimination and I was not. When my brother was 16, a police officer threatened to shoot him and his black friend. When I was 16, the police officer let me off without giving me a ticket because I started crying when I was pulled over. Factors such as location and physical characteristics can significantly alter the experiences of mixed-race people.

When it came to joining the conversation about racial injustice, I felt unqualified to speak and at the same time overflowing with things I wanted to say. While I cannot speak for all multiracial people, I believe that belonging to two worlds gives me greater leverage when having difficult conversations about race. Whether they like it or not, whites feel free to ask me questions about race. For example, questions like: "Why am I ......?" Please explain why I am ...... Please explain why I am ......" or "Do you think it's okay for me to ...... I don't think I am always qualified to answer, but I am always willing to try. I don't always feel qualified to answer, but I don't mind having those conversations.

But it can be exhausting for many. Kenya Cobb, 25, who lives and works in the Bay Area, is a person of color. She believes that educating her friends is often a burden because she is multiracial: "How many white people are in my circle and how important it is for me to speak up because they listen to me: ...... I should really listen to any (person of color)," he said. This circle of influence often extends to white families, as publicist Kristy Corso, 24, who is half Filipino, told me. She has made strides to educate her white father about the importance of racial equality and justice in films and documentaries highlighting the black American experience. Mary Katherine Withers, a 24-year-old announcer who is also half Filipino, believes her privilege comes with a responsibility to "speak out against racism and call people out when they are acting unacceptably."

Finding one's place in the fight against racial injustice is difficult. The role of multiracial people, in my opinion, has not been fully explored in this country. My white classmates could not understand how I fit in with them because they did not want to hear me talk about my race. I look white, so what do I know about issues surrounding racism, Latin America, and immigration: you should not be part of the discussion. But I know a lot about these issues through my own lived experience. As complicated as our racial identities may seem, not participating in the debate is not an option. When it comes to fighting racial injustice, I don't think being biracial changes anything: ...... I have no delusions about where I fit in what is happening in the world today: ...... It is everyone's responsibility, regardless of race, to do everything they can to tear down these institutions"

.

When I was younger, it was difficult to claim the privilege of being white without feeling like I was losing part of my Latino identity. I spoke Spanish before I spoke English and grew up surrounded by Nicaraguan relatives, but somehow acknowledging my privilege felt like distancing myself from my family history. I had witnessed overt racism directed at Nicaraguans and dark-skinned relatives, but rarely experienced it myself. This created a sense of guilt and made me feel unworthy of participating in the larger conversation.

On this topic, Rohrick has a word: "We are still people of color and our identity should be our own: ...... We are our history, our heritage, our mother's daughters. We are part of the conversation."

To read more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

Sign up here

.

Comments