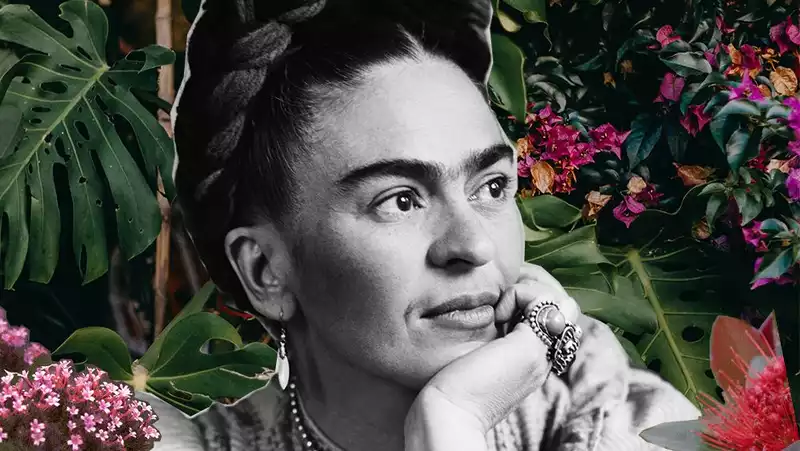

How Frida Kahlo Inspired Latinas to Speak Spanish

I spent nine months working on the first draft of my debut novel, What Would Frida Do' A Guide to Living Boldly (opens in new tab) (October 20). In between countless late nights at the keyboard and weekends spent poring over books about her art, I also spent time in Mexico City. Visiting Kahlo's home, La Casa Azul, and exploring Coyoacán, where she lived, were important to me. To see the world through Frida's eyes.

It was daunting to add to the already existing array of wonderful books about Frida, one of Mexico's most famous artists. But as a Latina, I felt an added responsibility to carry on the torch of Kahlo's legacy, and to carry it on well. When I read the revised draft of my book last spring, I was in awe that I had actually pulled it off.

Then I received an email from the publicist for my book.

"I forgot to ask if you speak Spanish and would be comfortable interviewing in Spanish," she wrote. Before I could finish reading her note, I felt a knot in my chest. It was the same tangle of anxiety that settles in the back of my throat every time a family member or stranger speaks to me in Spanish. I was writing a book about Frida, and as I struggled to explain my inability to speak her native tongue fluently, I flashed back to my time in Mexico City, and my heart churned with embarrassment.

With a sinking feeling in my stomach, I typed to my publicist: "Sadly, I am not fluent enough in Spanish to be interviewed."

For years throughout my career, I thought this would eventually happen to me. My mother is Puerto Rican, the daughter of parents who moved from the island to the Bronx, New York in the 1950s. When my mother eventually married my black American father and headed to the suburbs of Baltimore, Maryland, she had little reason to speak Spanish in our home, as no one she knew spoke Spanish. When we went to my grandparents' house, they spoke to us in Spanish and we responded in English.

It didn't feel like a big deal until I was older. I remember in college trying to pronounce the name of a Spanish song to a friend and feeling my face heat up as he burst out laughing." You're not Puerto Rican?" He said, his face turning red. It was one of many similar incidents over the years, often with people saying, "Oh, so you're not really Puerto Rican," or "Why didn't your mother teach you Spanish?" Over time, my inability to speak Spanish began to feel less like a circumstance and more like a deep-seated insecurity.

Thanks to social media and my time as a journalist, I learned I was not alone. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2015, only 73% of Latinos spoke Spanish at home (opens in new tab), and as of 2017, 22% of Latinos in the United States do not speak Spanish (opens in new tab). This is particularly true of Mexican-Americans and Puerto Ricans, which makes sense given that they are the first and second largest groups of Latinos in the United States (opens in new tab), respectively. It is also important to note that Puerto Rico is a U.S. colony and is more influenced by American culture and the English language than the rest of Latin America.

According to research (opens in new tab), one of the common reasons why languages are not transmitted across generations is assimilation. As a result, second- and third-generation Latinos like myself, who are proud of our heritage, often do not speak our ancestors' language fluently.

Still, after responding to the publicist that afternoon, I felt defeated. I knew I was not alone in my struggles with Spanish, but that did not make it any easier to admit it. At that moment, my eyes darted to the lock screen of my iPhone, where I saw the bright yellow cover of What Would Frida Do? Suddenly, it hit me: what would Frida do? I had written a guide on how to live boldly, inspired by one of the most daring women in history. It's time to take my own advice.

"Frida's fearlessness in the face of her shortcomings gives those of us who feel inadequate in the boardroom and in our relationships the courage to overcome imposter syndrome," I wrote in my chapter on confidence. 'She would tell us to always be our own biggest cheerleaders, even if we didn't believe it ourselves. After re-reading this passage, I decided to stop complaining about not being able to speak Spanish and finally do something about it.

After a few hours of research, I came across a program called Fluenz (open in new tab). In the midst of a pandemic, founder Sonia Gil and her team decided to replicate the usual face-to-face process in a six-week virtual immersion. Although she was hesitant about working remotely and attending classes three times a week, she knew that if she was going to be taken seriously, she needed to give it her all.

During the initial assessment, I took a deep breath to overcome my usual shyness and explained to the coaches, who were based in Mexico City but from Latin American countries, that my Spanish was intermediate despite being Puerto Rican. Gil, however, quickly reassured me.

"This is something I hear from a lot of students: I'm proud of my heritage and myself, and I'm better at understanding [Spanish] than speaking it, but I want to be able to speak it comfortably without hesitation," Gil says. Having taught for many years, she knows that "learning a language puts you in the most vulnerable position."

But the only way to learn a language, she adds, is to learn it. She says, "If you feel embarrassed because you have an accent, or you think you're going to sound like a toddler, that's okay. You may sound like a toddler. But eventually, that toddler will grow into a confident adult. It just takes time." [After all, I needed to write an entire book about an imposing and resilient woman in order to gain the courage to face my fears head on. But I decided to accept the challenge. Three times a week, after work, I held Zoom sessions with the Fluenz team. In between grammar and Spanish reading lessons, the teachers chatted with me. The teachers asked about my life, my work, my previous trips, how I coped with the pandemic, etc.

During the first few weeks, I stumbled over words and felt the familiar anxiety building up as I tried to remember basic phrases. But each time I stammered, I tried to remember the guiding question: What would Frida do? I envisioned my future self talking to reporters on the phone or on TV, speaking confidently about my book in vivid Spanish. Then I would take a deep breath and just talk. As I immersed myself in the conversation, I thought less and less.

One night after class on a Friday night, I hopped in an Uber for an outdoor meal with a friend. The driver immediately began small talk and we chatted casually. It took me a few minutes to realize I was speaking Spanish, but it came naturally to me. For the first time, I didn't overthink it and my cheeks didn't turn red. When we broke off the conversation, he turned on the radio and hummed a salsa song by Héctor Laboe, a favorite of my mother's. As I gazed out the open window at the New York City skyline, I realized that the grip on my heart had vanished into the night sky.

After six weeks of virtual lessons, I am not fluent. (To be fair, Gil says it's basically impossible to become fluent in six weeks.) But since that night, I've felt my confidence grow every time I speak Spanish with friends, family, or even strangers. Instead of assuming that everyone is ready to laugh at me, after all, everyone just wants to connect through shared culture.

So while I still have a long way to go before I feel ready to do every interview about Frida in Spanish, I am proud of my progress. I'm proud that I took the first step, that I put myself out there, and that I'm typing these words. And I think Frida is proud of me too.

.

Comments