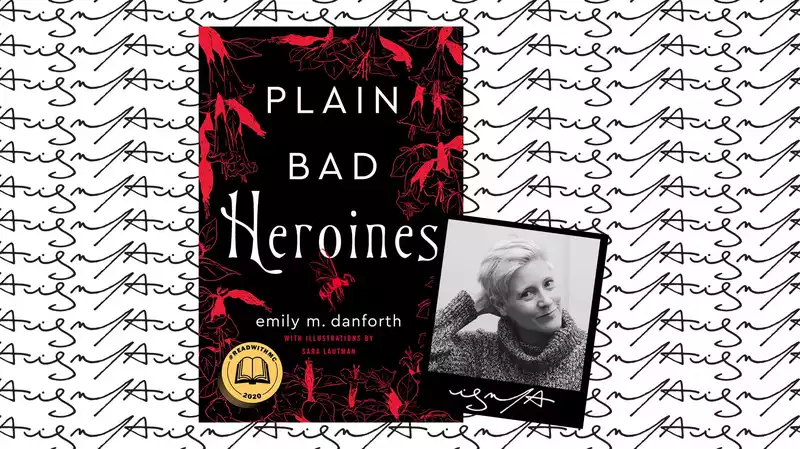

Marie Claire's November Book Club Pick for "Plain Bad Heroines"

#ReadWithMC (opens in new tab)-Welcome to Marie Claire's Virtual Book Club. Best regards. The novel begins in 1902 when Flo and Clara, students at Brookhants School for Girls, found the Plain Bad Heroine Society and are soon found dead on the school grounds. Read an excerpt from the novel and learn how to join the virtual book club here (opens in a new tab). (1]

In the novel's opening chapter, set in 1902, Brookhants School for Girls students Flo and Clara, in love with each other and with Mary McLean's journal, are violently killed by a swarm of wasps. It is said that the school's curse then begins.

In early December, [Mary McLean's missing journal was found with] Eleanor Faderman. Eleanor was wary (or jealous...) of Flo and Clara. This was when Flo and Clara were alive.

Eleanor Faderman actually tried to buy herself a copy of "The Mary McLean Story," which had made a big splash on campus the previous spring, but it was nowhere to be found in the bookstore she visited during her summer vacation.

Eleanor Faderman was short and petite, her features sharpened to the point of almost dotting, and her hair was a strange color, as if it were supposed to be brown but had lost most of its pigment to a dull brown. More importantly, Eleanor Faderman was known among her classmates for her talent with her thieving fingers, her curiously quiet presence, and her ability to move in and out of space without being noticed. Students in her dorm often noted this: where did you come from, Eleanor? Or vice versa: Eleanor, where did you come from?

Given these abilities, it was not difficult for Eleanor Faderman to steal a copy of the book that had returned with the body and keep quiet about it as well. The only reason she took the chance was due to the carelessness of Pinkerton, whom Flo's mother had hired to investigate her death. The detective had been looking through the book disinterestedly while waiting to tell Principal Libby Brookhunt about the tragedy. Clara and Flo's deaths were of course gruesome and horrific, but he believed that they were also cruel accidents of nature. When the principal finally opened the door and invited him in, the detective placed a copy of the book on the table outside the principal's office.

Our Eleanor Faderman watched him do so. And the book became hers.

Eleanor hid it behind a potted cupboard in the Brookhants Orangerie*. Seven mornings a week, Eleanor spent at the Orangerie tending to the plants and, in the winter, working on the elaborate and fussy heating system, stoking the wood. Most mornings, she was the first to light the gas lamps, if the pre-dawn twilight was not enough. (Some buildings in Brookhants had been electrified by then, but not the Orangerie.) Once visible, Eleanor donned her work pinofore, watered, fed, and removed pests, and removed wilts and deformities from branches and stems.

*If you are unfamiliar with it, think of an orangerie as a kind of fancy greenhouse/greenhouse. Before his death, Harold Brookhunt insisted that the school cease its involvement in the construction project and be named "Orangerie." (Harold Brookhunt was a French-lover. She would cut and bundle herbs and pick ripe fruit to send to the kitchen staff later. She did this only if the cook had left a note with the number of thyme sprigs or chives needed for that day's meal. And most mornings, the cook would leave her a note, despite her classmates' complaints about the tastelessness of Brookhunt's cooking. With scissors in hand, Eleanor wandered through the rows of fragrant, dense herbs, rejoicing in her small harvest, carefully bundling them and placing them in a basket next to the note with their names on it.

Eleanor Faderman also sneaked some fruit for herself on such mornings. It wasn't often, though. A ripe orange hanging from a tree branch in the gray snow of a Rhode Island winter was a kind of miracle. Even the students at Brookhunt School, who spent little time at the Orangerie, were understandably up in arms when they thought their classmates were stealing their orange bounty. But Eleanor never took her eyes off the occasional lime hiding in the bright leaves growing on the trees. Except for Miss Trillus.

Miss Alexandra Trills (as dull as she was tall. But Miss Trills would never say. Perhaps. (If you believe that such a crime was committed only once, you probably would.)

*I promise this is the last time I ask, dear reader, but please remember this name.

There were many morning tasks, but Eleanor Faderman made them a routine and usually made time for herself to finish them before breakfast. Imagine the joy of having a space like Orangerie all to yourself. Especially in a place like Brookhants, where fellow students are everywhere, shouting in the hallways, snoring in bed, blowing their noses in the bathroom, and whispering secrets behind your back in the classroom. Eleanor Faderman went from a house full of sisters to a boarding school full of students. And can you, dear readers, blame her for spending her own quiet time each day in the most beautiful place on campus?" where fuchsia flowers drip from planters, where students recite poetry in front of shelves where poet jasmine grows on the vine, where sunlight, glass, and green and everywhere, the scent of flowers in the air.

As the sun rose and the windows of the Orangerie filled with light and brilliance, Eleanor sat down in a corner she had found behind a huge zinc planter with a stolen lime, a piece of bread she had saved from the previous night's meal, or a single spearmint leaf. (14]

Here Eleanor could see from the wedge, without being seen. Here she could daydream while sucking on a mint leaf. Here she could study Latin (Latin is such a pain in the ass) or write a letter to someone back home (perhaps her sister Carrie). Here she might read, and often read it, and comfortably immerse herself in another world, another time, and another self.

Here she observed people coming to the Orangerie without being aware that she was watching them. Miss Trills checking out the freesias, or Grace O'Connell, who was wandering in the morning, and other students she thought were friendly and respectable sophomores. Eleanor thought so, too. Inwardly, she thought.

Grace O'Connell had a broad, pleasant face and a heart-shaped mouth. Grace O'Connell smiled easily, but this fact did not cheapen it. Eleanor thought Grace was lovely, especially when she thought Grace was alone. Like when she stumbled into the Orangerie just before breakfast and chewed the weight of a lemon, or when she stood in the warm sunshine with her eyes closed.

If Eleanor, like many Brookhants students, was the type to give her classmates bags full of candy and hairpins, Grace O'Connell would have been the classmate to give them. Or she could have given a bouquet of flowers. Flowers were still popular among the Brookhants girls. Mary Perrill, Eleanor's dorm mate, had the latest flower dictionary and was always reading it out loud. Yellow acacia for secret love, spearmint for general warm feelings, and tulips for communicating one's feelings. Eleanor Faderman, however, did not participate in the elaborate courtship rituals of her classmates. Nor did she send tokens of affection. Nor did she write a poem proclaiming her adoration and practice reciting it in front of Jasmine. Nor did she pick a bouquet of flowers to present.

She kept her secret feelings to herself.

There were other students at the Orangerie whom Eleanor might or might not have seen. Where she could not see herself, in other words, they were watching her.

Flo. Clara.

Flo and Clara were together and thought they were alone.

From "Plain Bad Heroines" by Emily M. Danforth. Text copyright © 2020 Emily M. Danforth. Illustrations copyright © 2020 Sarah Rothman. Reprinted with permission of William Morrow, an affiliate of HarperCollins Publishers.

If you prefer audio, listen to some of the excerpts below and read the rest on Audible (opens in a new tab).

.

Comments