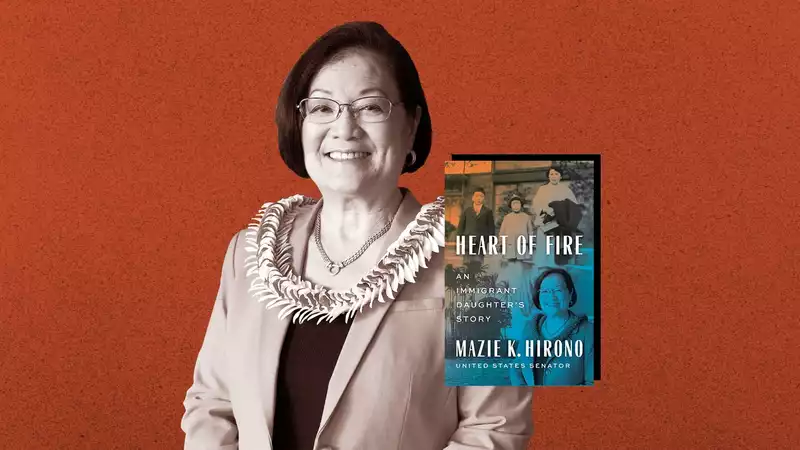

Senator Hirono on his journey to the Senate and having a "heart of fire"

[She said goodbye to her grandparents, her three-year-old brother, the gingko tree, and her only life in Fukushima. Then seven-year-old Keiko Hirono (later Mazie K. Hirono) boarded an iron ship with her mother and older brother on a March afternoon in 1955, heading across the Pacific to a new life in Hawaii. Without her mother, Laura Sato Hirono, who made the decision to move her family to her birthplace to escape her husband, who was known for his alcoholism and gambling, Mazie K. Hirono would not have become a member of the Hawaii State House of Representatives, Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii, or a U.S. Congresswoman, or the first Asian American woman and Japanese immigrant to She may never have become a U.S. Senator.Nearly 70 years after making her home in the United States, 73-year-old Congresswoman Hirono will publish her memoir, Heart of Fire, which will be released tomorrow. The memoir, which her husband encouraged her to write, is both a detailed account of the senator's life and an ode to her mother, who, as Senator Hirono writes, "never wavered in her belief that I could make my own choices in any life." Her mother, she says, was the person who best embodied this "heart on fire," this fighting spirit of determination, perseverance, and resilience.

Heart of Fire is shared with the world exactly one month and one day after Senator Hirono's mother passed away at the age of 96. Since my mother was in such a state, I thought it would be a good opportunity to tell the story of my mother and grandmother.

In advance of the book's release, Senator Hirono spoke to Marie Claire from her home in Hawaii about her reputation in the Senate, the special moment she shared with Dr. Christine Blasey Ford after the Kavanaugh hearing, and how we can invoke the "heart of fire" in all of us.

Marie Claire: Was there a particular moment in your life when you realized you had a "heart of fire?"

Mazie Hirono: One of my favorite poems is "The Road Not Taken" by Robert Frost." The poem "Two roads diverged in a wood, and I took the one less traveled by" describes my feelings very well. For me, it was a journey of doing things differently, but I always had the support of my mother. My mother knew that she did not have a daughter who would marry and fulfill the traditional role of a woman in my time. Therefore, on one occasion (I think I was 30 at the time), my brother said to my mother, "You know, I'm not sure I'm the kind of person who would have married a woman of my age. My mother never pressured me. She just encouraged me to do something different, like being a politician. Because at that time there were not many women participating in politics or campaigning for elections.

MC: In your book, you talk about how being a wife and mother was never your goal.

MH: Yes, even if I had a very courageous and independent mother, there is the expectation of the dominant culture. Our professions are probably like teachers and nurses. Both are very wonderful professions, but I wasn't particularly interested in them or felt I could do them. When I read "Female Mysticism" (opens in new tab) I thought a light bulb had gone on. That's when I decided to stop expecting men to take care of me.

MC: You seem to keep your cool no matter how tough the going gets, especially with the difficulties of campaigning and fundraising. Was there anything in particular that was difficult for you when you wondered if you could continue in public office?

MH: Once I decided to pursue public office, I was determined to do everything I could during my term. I know a lot of people who are always looking for the next big race and planning for it. I didn't do that, and when I made that decision, my life was much more difficult. We should not be waiting for "when I get that position" or "when I get that chairmanship." Forget about such things. Just do what you can do here and now.

My husband and I often talk about how (no one) would have predicted that I would end up in elected office for most of my adult life. I didn't predict it, but I was determined. So I feel very fortunate to be able to do this. My high school classmates say to me, "I didn't know you were interested in politics." Well, I didn't manifest everything in high school. I went to college and protested the Vietnam War because it was a great experience for me.

MC: With the surge in hate crimes against the AAPI community, compared to other senators, do you feel a greater responsibility to work toward a solution (opens in new tab)?

MH: There is definitely a connection to AAPI, which is being targeted randomly in these types of attacks. However, my expectation is that everyone should be completely concerned about this type of attack against any group, regardless of whether or not they share the same racial background. What I don't understand is why more people don't speak up, especially on the Republican side. But I feel connected and feel a responsibility to speak up. I have never seen so many AAPIs on TV as I do now.

MC: A big theme you write about is anger and what it means for women to be angry. Do you think that if you had been "angrier" earlier in your career (before the Trump administration), you would have built the same kind of reputation that you have now?

MH: I have always considered myself a fighter. I can be very harsh with people, and I had a reputation in Congress as the "ice queen." But I was never very loud about it. So I would laugh when people would say, "She found her voice." I always had a voice. I get a lot of angry reactions to what I say, but it doesn't really bother me because I'm going to keep saying it. I think it's important now for people to know that their elected officials are fighting for them.

MC: In your book, you mention that Dr. Christine Blasey Ford contacted you while on vacation in Hawaii after Brett Kavanaugh's confirmation hearing. I am very grateful to Dr. Blasey because, like many other American women, I often think of her and wonder how she is doing. This anecdote has given me comfort.

MH: Yes. She told me she was fine. I was very surprised when she asked to see me because she wanted to thank me. I said, "I am grateful to you. I had heard so many negative things about her. What happened to her in that whole process was really terrible, but that's what she pointed out. We still have a ways to go.

MC: Right. And the fact that you remembered making eye contact with her at the hearing is powerful.

MH: Because that's the kind of person she is. She wants to connect. She tried to connect with all the members of the committee. By the way, Kavanaugh never did that. The Kavanaugh hearings had people from all over the world riveted. I describe (in my book) how my European friends were in the audience. They never left their hotel rooms. They were glued to the TV. Many people were watching closely to see what the US was going to do in that situation.

MC: Immigration reform is important to you, along with education and labor. Do you have any specific goals or policies that you hope to achieve by the end of your career?

MH: One of the first things I want to do is help Joe Biden get this pandemic under control and get the economy back on track. This means pushing hard for infrastructure legislation (opens in new tab) that will create jobs and long-term benefits, and it also means dealing with climate change and doing something about racism in our country. These are matters of great concern. I tell my staff all the time that people in this country are being hurt badly every second, every minute, every hour. If we can reduce that number through our efforts, we will make a difference.

MC: You talk a lot about your mother's legacy. What would you like to do with your own legacy?

MH: I am not looking for some big legacy project or anything like that. Because I also understand that all the battles we thought we had won for women's right to choose and to vote will not end up being won. Eternal vigilance is required of all of us. It is my hope that those who read this book will be encouraged to speak out and show up. Half the battle is showing up. We can all speak out against racism. We can all speak out for equality. And I believe that the fighting spirit, the "heart of the flame," is in all of us. I hope my book and what I do (in my daily life) will encourage people that they too can take this journey. Every person has a story to tell about the challenges they face. If that leads us to be more compassionate and accepting of others, then that is a good thing."

This interview has been edited and summarized for clarity.

.

Comments